Decoys are visual aids used to draw attention, give birds and animals a reason to close the distance, and to add realism to a hunting ambush set-up. Setting up duck decoys placement, posture and movement (or lack of motion) can all be important. When hunting waterfowl, positioning of your decoys in relation to the hunters’ locations and considering the wind speed and direction is vital for consistent success.

As migrating birds move south, they look to flock with other birds. We hope that our fake offering of companionship appears appealing enough to draw them close enough for a second look. The time of the season, the species of waterfowl, hunting pressure, and whether you’re hunting on the water or field hunting can all make a difference on the type of decoy set-up that will work best.

Decoy placement is something I believe many waterfowl hunters don’t fully understand. Many hunters simply scatter their two dozen mallard decoys over a wide area out in front of their position, and this may work. However, these waterfowlers probably haven’t spent much time watching real ducks on the water or how new ducks act when they’re coming into land amongst them. It depends on whether they are feeding or roosting, but pay attention and you’ll begin to see some patterns.

Giving them a “landing zone” is one of the most important aspects if you really want ducks to decoy. If you just want them to “buzz” your spread, placing them out indiscriminately will work, but there’s nothing like shooting at ducks with their wings cupped that are committed to a spread.

CLP Media

As far as placement of goose decoys, some experts will tell you that you need to face them all strictly into the wind. I do agree with that somewhat, however, watch a flock of geese feed sometime. They may be facing every which way. I like to place goose decoys in random smaller groups within the larger formation and vary the position. It seems the stronger the wind, the more you want to adhere to facing them into it – and just as with duck decoys; you must leave a landing zone.

Movement it is definitely another key – many have believed this for some time. Like others, back in the day we used to throw rocks near our decoys to create a ripple on the water when birds were coming close. Obviously, now days pitchin’ rocks isn’t necessary. We have swimming decoys, wing-flapping decoys, and decoys that create a ripple on the water for you – even a simple jerk-line will create ripples and the illusion of live movement. There’s no question this motion helps. When field hunting, the same types of motion decoys are available, otherwise, get yourself a goose-flag and learn how to use it.

How Many Decoys to Use?

I’ve been on hunts that ranged from setting a few decoys in a small slough or pothole for dabbler ducks, on up to having to rise from a drooling sleep at 2 am just so we had enough time to set out hundreds of goose decoys before sunrise. Generally, puddle duck set-ups will use the fewest decoys – usually a couple dozen or less will suffice, but you can certainly use more. Diver duck set-ups will customarily have larger sets. Since these set-ups are usually on much larger bodies of water that makes sense. Some diver spreads may have 100 decoys or more.

kostakirov

Then we come to goose set-ups. From my experience, it depends upon the species of goose hunted, the time of the season, whether the birds you’re hunting have experienced hunting pressure or not, and whether you’re field hunting or on the water. When trying to draw in large flocks, I normally like lots of decoys…but there are exceptions.

The people I’ve hunted snow geese with will often pull a horse trailer to accommodate all the decoys they have…easily hundreds. The spreads are often made up of several different types. In one spread you may have full-bodied, shells, windsocks, silhouettes, flags and possibly motion decoys (where and when legal). When you are trying to attract flocks of a hundred or more snows and blues they may not give a small spread of a dozen decoys a second look.

With Canada geese, I‘ve seen it vary widely. Much depends upon whether the birds have experienced hunting pressure. In Manitoba and Saskatchewan we’ve used some large sets of a couple hundred decoys. Remember though, most of the birds that far north haven’t experienced much hunting pressure, and you may be trying to be noticed from a long distance so larger sets seem to work well.

Fred Zink, one of our Nation’s top waterfowl hunters, has a great tip. When hunting Canada geese, Fred likes to use silhouette decoys along with several other types of full-body decoys. He says he places the silhouette decoys very close together. Because of the contrast of light and dark colors and the shadows when geese are flying by and one decoy passes behind another, it gives the illusion of movement amongst your spread.

In contrast, I’ve also seen large sets spook Canada geese. Around my home in Minnesota, after the first couple of weeks of the season the birds become “educated.” In this case, smaller, ultra-realistic looking set-ups are necessary. You wouldn’t think a Canada goose as being smart with a brain the size of a walnut, but after getting steel-shot flailed at you a few times I suppose you wise up quickly. For late season sets, we will normally use two dozen decoys or less, and they’ll all be very convincing looking full-bodied decoys.

Where and How to Use Decoys?

There have been many names given to various decoy configurations and we’ll look at a couple. But really, in my view, they’re all very similar. The decoys’ purposes are attraction and blocking. “Blocking” means if the decoys are occupying a spot, then the live birds cannot land right there. We want them to set down in an area of our choosing. The important details are going to be the wind direction and speed, and that you leave a space where they can land. Ideally, some scouting will have told you the area(s) the birds have been using – that’s where you want to be if possible.

When airplanes take off and land, they use the wind for lift and resistance – so do waterfowl. Just as airports have runways in varying directions, waterfowl will use approach vectors that vary depending upon the wind direction and speed. When landing, they cup their wings to create drag and slow themselves, and whether they’re landing on water or land, they touchdown feet first.

While there are many exceptions to the following rule, generally, you’ll want to position yourself with your back to the wind so you can clearly see a flock’s final approach. I tend to be a bit better shot when swinging to my left, so I often try to position myself with the wind angling over my left shoulder. Oftentimes thermals or wind changes will make it necessary to move your position or adjust your decoys. Just play how the birds are reacting to the conditions and your set-up.

The following decoy set-ups can be used on water or on dry land. While other names have been given to various spreads, most are just variations of the following.

Slot Pattern Decoy Spreads

A slot pattern can be made up several ways. Again, the important things are that you pay attention to the wind direction and that you leave a landing zone for the birds. The “slot” is the space that you leave between a divvied up decoy spread. It’s really only limited by your imagination and how many decoys you have.

One slot would mean you have your decoys divided into two groups in front of you, one group in front to the left and one to the right, with the wind at your back and a landing zone, or “slot,” between the two bunches of decoys. You can leave more than one slot by dividing the decoys into thirds. When using them in thirds you can leave two landing zones, one between the 1st and 2nd group and one between the 2nd and 3rd group. You can also use the 3rd group as a “stopper” or “blocker” for the landing zone. Where you position would depend upon how many hunters there are, how hard the wind is blowing and how many landing zones you leave.

One slot would mean you have your decoys divided into two groups in front of you, one group in front to the left and one to the right, with the wind at your back and a landing zone, or “slot,” between the two bunches of decoys. You can leave more than one slot by dividing the decoys into thirds. When using them in thirds you can leave two landing zones, one between the 1st and 2nd group and one between the 2nd and 3rd group. You can also use the 3rd group as a “stopper” or “blocker” for the landing zone. Where you position would depend upon how many hunters there are, how hard the wind is blowing and how many landing zones you leave.

J-Hook Decoy Setup

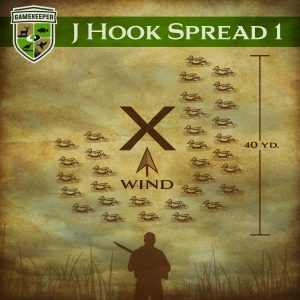

Just as it sounds, this decoy spread resembles a “J” or fishing hook. This pattern can be used for puddle ducks or diving ducks on open water. Similar spreads will work for geese when field hunting, too. It’s made up of decoys that start in a long line, then turns out, and curves into a hook. This creates a long blocking line the birds will follow with an open pocket in the middle as a landing zone. When setting up a J pattern, the bottom of the “J” should be into the wind and the hook curve away from the wind.

The “J” forces the birds to follow the string of decoys into the opening the “J” creates. This pattern can be moved around a large pond or open water depending on the wind direction, and the hunters can also be repositioned depending on the birds’ patterns on that day. The J is normally hooked towards the blind or boat. You hope that the birds will land in the open space and want to add to your fake birds at the end of the hook – typically, that’s where the best shot opportunities will be.

The “J” forces the birds to follow the string of decoys into the opening the “J” creates. This pattern can be moved around a large pond or open water depending on the wind direction, and the hunters can also be repositioned depending on the birds’ patterns on that day. The J is normally hooked towards the blind or boat. You hope that the birds will land in the open space and want to add to your fake birds at the end of the hook – typically, that’s where the best shot opportunities will be.

Decoys are great, but scouting, more than any one detail, is the most important measure towards success. You need to know the birds are there, where they’ve favored feeding or roosting and then the best spots to get close to them. Even if you have your own lake or impoundment, learning the patterns and where the waterfowl like being during different conditions is important. If you do your scouting, and then apply the advice regarding set-up and decoy placement, success will follow.