When the first Europeans landed in North America, wolves were ubiquitous, reigning supreme at the top of the food chain from coast to coast and what would eventually become Canada and Mexico. In the blink of a geological eye, we all but wiped them out. Efforts to restore wolves in North America have been underway for some time now, and with them has come considerable controversy. It might be easy for us as gamekeepers to expound on their impact on “our” resources, but we also need to understand the importance of conservation and population dynamics. If nothing else, when you have to stand up in front of a room full of people and plead your case against wolves, or coyotes, you’ll want to make sure it’s sound.

Taxonomy and History of Wolves

“Wolf” can sometimes be an over-generalized term so some background will help in understanding just what we’re talking about when we use it. Bear in mind that trying to distill wolf DNA down to simple terms can be challenging; but here goes.

Geoffrey Kuchera

According to the generally accepted theory, North America canids share a common ancestor, (Canis lepophagus). Some emigrated to Asia, then Europe, where they evolved into the gray wolf (Canis lupus). Those that remained evolved first into the smaller eastern North American timber wolf (Canis lycaon); and about 300,000 years ago, some diverged into the western coyote (Canis latrans). Meanwhile, gray wolves returned over the ice bridge and re-established themselves in the northwest. By around 500 years ago, gray wolves occupied most of Canada, while timber wolves dominated south of the Great Lakes and coyotes proliferated in the west.

Man’s influence on North American wolf populations began when changes in the landscape (deforestation) led to gray wolves receding northward and timber wolves moving into the void, following the expanding deer herds. Further human encroachment, and along with it bounties and an overall dislike for most any large predator, eventually led to a relatively rapid extirpation of wolves from the eastern U.S. Nature abhors a vacuum. Western coyotes expanded east to fill the void, and made some interesting friends along the way.

The Decline of Wolves in North America

The Decline of Wolves in North America

Where eastbound coyotes encountered wolves, both populations were low. When that occurs, individuals will sometimes breed with other species if they can’t find a mate of their own. While the exact nature of these interactions is unclear, we do know that coyotes carried a diverse array of DNA as they continued eastward.

Eastern Coyotes and Wolf Hybrids

The proportion of wolf DNA in northeastern coyotes varies considerably. However, they are physical and behaviorally different than their western ancestors. On average, they’re about 10 pounds heavier and exhibit more color variation. They have larger bodies, skulls and jaw musculature more suited to taking down and eating larger prey like deer, which they do regularly. While they may look like little wolves and even carry some of their genes, they are a distinct species referred to as the eastern coyote.

The lines become further blurred when you add red wolves (Canis rufus). Some taxonomists consider North American wolf lineage to contain only three species: gray wolves, red wolves and coyotes, dismissing the eastern timber wolf as a hybrid of gray wolves and coyotes. Further complicating things is DNA evidence suggesting red wolves are more closely related to coyotes than gray wolves. And all of the above is just a very cursory explanation.

Regardless, humans and the wolves themselves have been trying to restore populations to their former haunts for quite some time. One of the earliest examples and longest studies began in the 1940s when wolves crossed an ice bridge from Canada to Isle Royal, Michigan. Researchers hoped the natural introduction would ultimately demonstrate a restoration of the “balance of nature” between moose and wolves. They observed quite a different result, one that would ultimately provide a much better understanding of predator prey relationships.

Wolf Reintroduction Efforts and Challenges

It seems that nature prefers dynamic variation rather than balance. With an abundance of prey, predator populations grow until predation rates exceed prey production. Prey populations plummet, and with less prey, predator populations follow suit. When prey populations recover, the cycle begins again, theoretically.

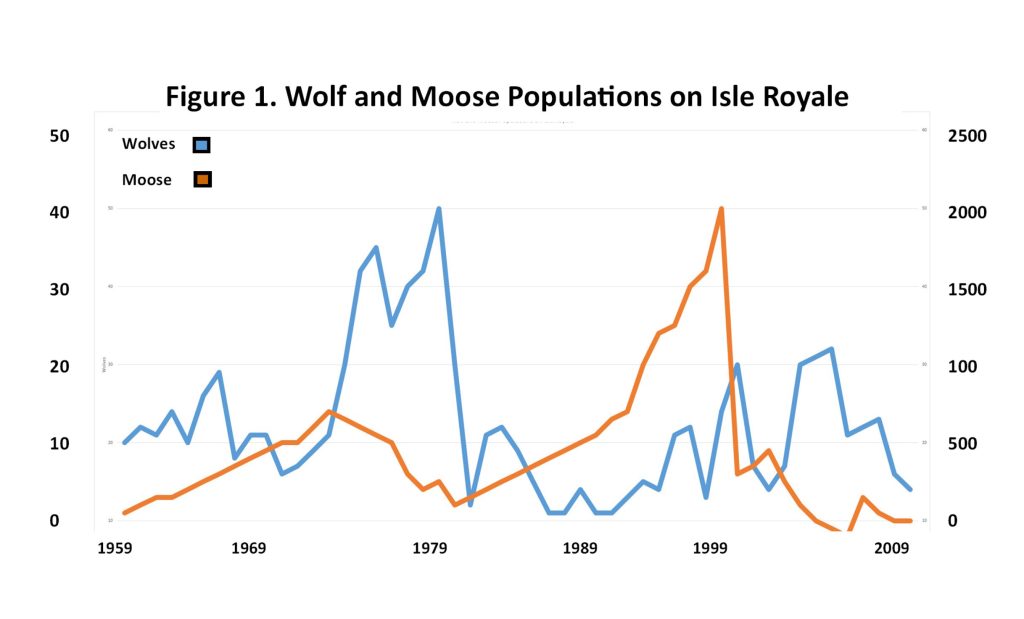

Even that is not so neat and orderly. Over 50 years of research on Isle Royale has seen both moose and wolf populations fluctuate dramatically and in some unexpected ways, partly due to suspected inbreeding in wolves and over-browsing by moose (see Figure 1). In the final analysis, researchers compared their predictions about wolf-moose to those for long-term weather and financial markets.

Wolves began re-establishing packs in northwestern Montana in the 1980s. The earliest and most noteworthy effort by humans occurred in 1995 and 1996 when 31 gray wolves from western Canada were released in Yellowstone National Park. A decade later, wolf populations were established in Montana and Idaho to the point where management authority was transferred from the federal government to those states. Five years later, The U.S. Fish and Wildlife removed wolves from the endangered species list in those states as they had met population goals of the recovery plan.

That, and similar actions remain a significant source of controversy. Wolf protectionists tout the Endangered Species Act as the best means for promoting recovery of wolf populations, and lobby hard for listing. The Act requires a population assessment and a recovery plan. According to the Act, once populations goals are met, the species is to be de-listed — mission accomplished.

However, the pro-wolf side isn’t satisfied. Lawsuits and court injunctions delay de-listing. Meanwhile, wolf populations continue expanding in size and range, increasing their impact on game populations, livestock and humans.

The Impact of Wolves on Ecosystems

Wolf re-introduction in Yellowstone National Park provides another example of direct and indirect consequences. Prior to reintroduction, elk were abundant enough that they taxed the carrying capacity, browsing heavily on preferred species like willow and aspen. When the wolves arrived, their predatory pressure prompted elk to be more mobile, reducing browse pressure. That, in turn, produced a bounty of food for beavers, and the number of active colonies has grown from one to nine. This had a cascading effect on hydrology, evening out seasonal runoff pulses, storing more water to recharge the water table and providing more cool, shaded water for fish and streamside cover for wildlife.

Wolves also altered the food chain. Formerly, the primary source of elk mortality was winter die-off, creating a boom-and-bust cycle of elk carrion that fluctuated in proportion to population size and winter severity. With wolves now the principal predator, carrion availability became more consistent, supporting scavengers like ravens, eagles, coyotes and bears, to name a few. Ecologically, the project could be considered a success, but wolves know no boundaries.

Linda Arndt

Why Wolves Matter: A Balanced Perspective

A lot of how someone feels about wolf reintroduction comes down to perspective — personal, geographical and chronological. The North American conservation movement was born mostly out of efforts to restore populations of game animals, like deer and elk. Over the last century or so we’ve done an incredible job of that, but similar efforts to restore predators are having a negative effect. Whether you support them often depends on which side of the food chain you favor, and promoting predator control solely so that we have more prey to harvest can be a logical trap.

There are sound arguments in favor of predator control. It may be warranted when predation rates reach a level where prey populations are in jeopardy, but how do we define that? Economic impact also needs to be considered as hunting is a huge economic driver in many places where wolves now prowl. We also need to consider how predators interact with and impact humans and livestock.

Historically, wolves ranging freely from Canada to Mexico weren’t much of a problem, until the westward expansion of people and the conversion of prairie to range. Cattle now claim the land where the deer and the antelope once played. One could argue that the wolves were there first, but the landscape has changed inexorably, and livestock depredation has become a seriously contentious issue.

Economic and Social Impacts of Wolves

Numerous sources suggest the impact is minimal, but that too can be a matter of perspective. On a nationwide scale, it is. But you might feel differently if it’s your cattle the wolves are eating. Research has shown the impact goes beyond predation. An Oregon State University study demonstrated the mere presence of wolves resulted in weight loss, lower pregnancy rates and increased stress in cattle. An Oregon Extension agent estimated the combined effect of depredation, sickness, weight loss and reduced pregnancy rates amounted to an average annual loss of $250-$300 per head for ranchers dealing with wolves. Extrapolate that on a per-herd basis and it could mean the difference between profit and loss.

Livestock aren’t the only critters in potential peril from predators. Due to increased incidence, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources has a special program devoted to dog depredation by wolves. They track depredation events, maintain an interactive map and issue advisories for certain areas. As of late September, there had been 19 incidents involving 25 hunting dogs killed by wolves in 2024.

Being a biologist, I tend to be trusting of state and federal wildlife agencies. But agencies are made up of people, and everyone is different. I recall a story that was related to me very early in my career, around the time wolves were first being re-introduced in the west. A certain agency person was instructed to “remove” wolves from an area where there had been high livestock depredation. The first animal he shot was the only one in the pack with a radio collar. My initial response was, “What could he have possibly been thinking?” Then I realized, that collar was the only way to locate the pack and potentially remove more wolves.

Red Wolves: Conservation and Challenges

No assessment of wolf interactions in North America would be complete without some mention of the species that rarely gets mentioned: the red wolf. We’ll skip ancient history because it’s mentioned above, and there’s still some disagreement on lineage. Jump ahead to 1972, when the species’ range was limited to a small area of the Gulf Coast in Texas and Louisiana. From 1973-1980, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) began trapping what they referred to as “wild canids,” to prevent extinction. Meanwhile, Point Defiance Zoo and Aquarium began a captive breeding program. Red Wolves were declared extinct in the wild in 1980.

From 1987-1994, FWS released 60 adult red wolves into Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge in North Carolina. The wolves formed packs, established territories and successfully bred. By 2012, the population was estimated at 120, but it wouldn’t stay that way. Human-caused mortality (gunshots, vehicle collisions) and hybridization with coyotes, resulted in a dramatic decline. There were no red wolf pup births recorded from 2019-2021 and the population is currently estimated at just over 20.

Perhaps it’s their low numbers and limited range that keep red wolves off the radar of most people, hunter and non-hunter alike. Maybe it’s because their impact is minimal compared to that of their close cousin. Again, perspective plays a part as red wolf proponents regard the current species status as a conservation success. One could argue otherwise.

Linda Arndt

Why Wolves Matter: A Balanced Perspective

The overriding goal of wolf reintroduction was and is to re-establish natural ecosystems and predator-prey interactions. The results show just how impactful those measures can be, though not always in expected ways. One on the wolf’s side might argue that reintroducing wolves is beneficial to prey species like elk, as thinning the weak, sick and old improves the health of the herd. Restoring prey densities to historical levels might also result in less impact to the habitat and thus, more and more nutritious food for those that survive.

The con side doesn’t necessarily care for the competition. Predator control programs and especially bounties and contests are always controversial. Hunters proclaim, “The coyotes (or wolves) are killing all our deer (elk, moose). We need to do something to control them.” That seems reasonable, but to what end? Do we want fewer predators and more deer so that we can kill more deer? That seems a little self-serving, and won’t pass the straight face test.

Conclusion: Finding Common Ground with Wolves

We were sitting in a wall tent on the shore of a remote lake on northern Quebec’s Ungava Peninsula when I heard a distant sound. “Stop, wait, listen,” I said to my camp mates. When we heard it again we rushed outside the tent, stood on the shore and in the glow of the aurora borealis, listened to a chorus of wolves howling.

If you’ve never read the book or seen the movie “Never Cry Wolf” you won’t get the reference, but I have no intention of ever taking off my clothes, running around the tundra and eating voles. However, there is, and needs to be a place for wolves. They are a symbol of a healthy environment, and of wilderness; and that is where they should live. It is when they encroach on our home range that we, like they, get territorial. We, as hunters, need to accept them where their presence is appropriate. We as a society need to accept that because of us, those places are far fewer and farther between than they once were.

Join our weekly newsletter or subscribe to GameKeepers Magazine.

Your source for information, equipment, know-how, deals and discounts to help you get the most from every hard-earned moment in the field.

The Decline of Wolves in North America

The Decline of Wolves in North America