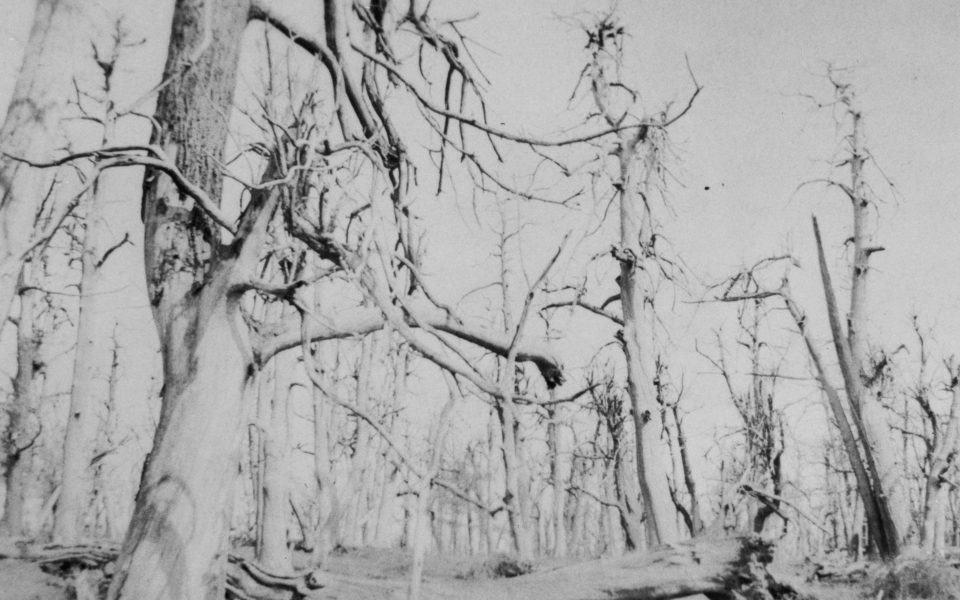

Squirrels in my region lived a hard life when I was a kid. I knew every nook and cranny where one might be hiding and one of my favorite haunts was a small grove of dead American chestnut trees on my grandfather’s farm. The trees had died long before I was around and all that remained of those old chestnuts from the 1960s were dead snags. It was a perfect home for squirrels that always seem to have had a well laid plan on avoiding being shot by a kid and his .410 Stevens.

My grandfather told me these old snags were what was left of the American chestnut trees that he had shot squirrels out of in the early 1900s. He told of not only shooting squirrels in those trees, but picking up buckets of chestnuts each fall which seemed to provide enough for the Hines family as well as the squirrels.

The American Chestnut Blight: A Natural Catastrophe

Richard Hines

I’m not sure he knew where the blight had originated, but he did see its immediate effect on forests in Kentucky. Caused by the introduction of plant stock from China a half a century earlier in 1904, when one of the arborists at the Bronx Zoological Park in New York City discovered a type of fungus on the park’s American chestnut trees.

As years advanced, 1904 was relatively uneventful with few historical events, but the accidental introduction of the chestnut blight (Endothia parasitica) would later be referred to as the greatest single natural catastrophe in environmental history. The blight, which is a canker disease that grows rapidly, eventually girdling and killing chestnut trees received the common name of “blight” because of its habit of acting quickly, killing branches and stems which is typical for an agent in plants called “shoot blight” hence the association with blight.

It is believed that the pathogen for Chestnut blight was brought in on nursery plant stock from either China or Japan where the pathogen is native. Chinese chestnuts both in China, the United States, and around the world are continuing to thrive and while Chinese chestnuts do get the disease, it appears to be very inconsequential. Chestnut trees in Europe have also had problems, but the European trees seem to be fairing slightly better than American chestnut trees.

The blight spread quickly out of the Bronx Zoo and at a rate averaging 50 miles per year began killing American chestnuts by the thousands. One source said, “The blight never met a tree it couldn’t kill.” By the end of the 1940s, 80% of all American chestnuts in the eastern US were dead or dying. One estimate stated that if all the chestnut trees that were alive in 1904, were in one location, they would have covered nine million acres of pure chestnut trees.

The Role of Chestnuts in Forest and Wildlife

Chestnut trees were very prominent in eastern forests and while there was some variation according to soil type, slopes, and other factors, American chestnuts comprised from 25% to over 60% of the total forest canopy. Chestnut trees did not grow in single stand forests but grew in association with other hardwood species. You may have heard foresters and biologists refer to oak-hickory forests. This association was originally called the oak-chestnut forest until chestnut trees disappeared.

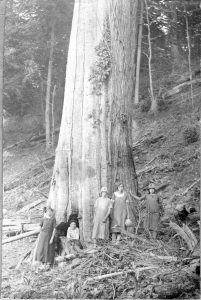

In addition to durability, chestnuts were stately trees; some authors referring to them as the “redwoods of the east.” American chestnut had a wide range, growing from the Gulf Coastal Plain north into Maine. Chestnuts did not grow as far west as Wisconsin but by the late 1800s settlers had already begun transplanting these trees into that region.

On good quality sites, chestnuts could grow from 60 to 120 feet tall and up to seven feet or more in diameter. Their growth was so fast that these trees could add one inch of diameter growth per year which added up to 500 board feet per acre each year. From the standpoint of forest economics, the loss of these trees in today’s market would be valued in the multi-billions of dollars.

The American chestnut provided everything America needed. The first settlers into the Appalachians immediately built a chestnut log pen for temporary protection for them and their livestock. The log pen later became the center piece and support for the family barn. Split rail fences, cabins, and later telephone poles, furniture and even caskets were constructed from chestnut.

Wildlife and the Loss of Chestnuts

National Parks Service

From a wildlife standpoint, gamekeepers might wonder how this would impact wildlife. In almost all cases, chestnut trees were replaced by oak trees. Not a problem you say, everyone wants oaks, but here is what we lost when chestnuts dropped out of eastern forests.

With chestnut trees comprising up to 60% of the forest canopy, you could count on large quantity of chestnuts on the ground by late September. However, with the loss of chestnut trees, there was a long period of time without hardwood mast in forests. As the chestnuts died, gaps in the forest were quickly filled by oaks which could take up to twenty years to begin producing acorns. With the loss of chestnuts, it was well over two decades before any sizeable mast crop appeared. While oaks took up to twenty years to begin producing acorns, chestnuts could produce a small mast crop by year six. Additionally, oaks are not always consistent nor as abundant in providing mast as were the chestnuts.

In some locations prior to the blight, 96% of the mast crop in eastern forests consisted of chestnuts. But like oaks, chestnut production varied site to site with ranges of 30% to 96%. In early forests, oaks only provided around two to eight percent of the total mast. At least temporarily, almost all hardwood mast disappeared from the forests following the disappearance of chestnut.

Today, you will hear hunters ask “how are the acorns this year?” It is never the same and the variation changes year to year, species to species, and even farm to farm. Prior to the blight it was not unusual for chestnuts to outproduce all other species nine out of ten years.

Oak is also vulnerable to environmental factors, insects, drought, and late freezes. Late freezes were not an issue with American chestnut as they typically bloomed June to July.

Another factor is really an unwritten rule, you should have around an average of 100-pounds of hardwood mast per acre to sustain deer, turkey, and other wildlife. Again, this varies according to a wide range of factors each year. Some years and some sites can produce a higher number of oak mast, but for chestnut it was not uncommon for them to produce over 165 plus pounds per acre each year without failure. The quantity and consistency of the chestnut carried all forest wildlife species.

Restoring a Lost Giant

Richard Hines

Amazingly, millions of chestnut trees remain today, but they are no longer the large stately trees of the past, but only shrubs, most struggling to reach five to ten feet tall until they are killed by the blight. I have stood in patches of chestnut saplings that continually resprout from a tree’s original stump and roots that died over 80-years ago. The saplings are no longer the straight, fast growing tree my grandfather described.

Of the billions of chestnuts that were alive during the last century, three known American chestnut trees that were alive prior to the blight continue to survive. One of these trees, the “Adair Tree” in Kentucky is monitored by several researchers, a cooperating landowner, and retired Kentucky Division of Forestry District Forester Billy Fudge. Fudge said, “For some reason this tree continues living and producing fruit although it is not fertile. Chestnut trees are monoecious meaning they require two trees to pollinate the flowers each spring. Right now, the other two trees are in Pennsylvania and Virginia and efforts are made to transport pollen between the trees each year. These trees continue producing nuts if they are pollinated but the young seedlings growing from these nuts eventually succumb to the blight. Without pollination, the tree continues producing the needle-sharp burr, but the three nuts found in each burr do not develop.

Fudge said, “Chestnut trees were such an important tree…they produced everything we needed from housing to furniture…chestnuts not only fed us, but they fed our livestock.” Fudge added that his grandfather had told him that hogs fattened on chestnuts produced some of the best pork he had ever eaten.

Another group involved with the restoration effort is the American Chestnut Foundation. Researchers with the foundation feel they can revive the species but to make an impact on the landscape it may take 150 to 200 years after they find that one seedling that will not only be resistant but is able to produce progeny that is also resistant and can be transplanted into forests.

One of the reasons this species of blight is so deadly for American chestnuts is that “it [blight] has two different ways of reproducing and multiple ways of being transported.” Aside from being moved by birds, mammals, insects, and the wind, “it can even be consumed and move through the digestive tract of mites” and survive.

Richard Hines

With early restoration efforts beginning in the 1950s, the Chestnut Foundation is now involved with backcross breeding, moving desirable characteristics from one variety to another and across regions of the country in hopes of isolating blight resistant genes from another species. One of these genes is from the resistant Chinese chestnut. The problem is that offspring resemble the short and bushy Chinese chestnut and in no way reaches the characteristics of the American chestnut. This is because so many genes must be transferred from the Chinese chestnut to provide resistance that it causes the offspring to resemble the Chinese species.

Fudge said that researchers in New York are using genetic engineering to “develop a blight resistant tree by combining a single strand of DNA from wheat with the DNA of American chestnut.” Fudge was optimistic about the success researchers were having and said, “When blight hits a tree, it immediately starts producing oxalic acid which kills cells in the tree…the dead cells are what the fungus lives on, and the inserted wheat gene produces another enzyme that detoxifies the acid.” During the process provided by the wheat gene, acid is converted into carbon dioxide and hydrogen peroxide which is harmless to the tree.

The result is a genetically engineered tree referred to as “Darling 58.” Even with this new gene, the trees can still become infected but at this point most seem to be surviving. Since this tree is genetically engineered, it is only being grown in a regulated area where any chance of it pollinating other plants is not possible. Currently, the USDA and other federal agencies continue reviewing a petition that will allow researchers to begin planting these trees in normal forest conditions. Only then will we know if this method will be the answer.

Looking ahead, other researchers are beginning to study effects of prescribed fire in stands of chestnut saplings, the amount of light required for growth, all in anticipation of starting the first new stand of chestnuts.

Researchers with the American Chestnut Foundation and others agree that there are no trees that are immune to the chestnut blight. The reason, all trees will get the blight, but some species are resistant. It just appears that we must find that first tree to begin the process, a process that really can’t start until these trees reproduce on their own and their offspring in turn began producing trees. Then, and only then will we have a population of American Chestnuts back on the landscape.

Richard Hines

Hope for Generations to Come

I had a glimpse of what our early forests looked like when I hunted squirrels in that old chestnut stand on my grandparent’s farm. The old snags were impressive, and I remember how close some were to each other, massive trees within a few feet of each other, but they are gone, and no one today can visualize what our eastern forests once looked like or what it was like to walk among these giants. I would like to think that my great, great grandchildren might be fortunate enough to see them.

References

Journal of the American Chestnut Foundation. March-April 2012 Issue 2 Vol. 2. 22pp.

Powell, William A., et.al. 2019. Developing Blight-Tolerant American Chestnut Trees. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Biol doi:10.1101/cshpersect. A034587

Join our weekly newsletter or subscribe to GameKeepers Magazine.

Your source for information, equipment, know-how, deals and discounts to help you get the most from every hard-earned moment in the field.