If you follow the MSU Deer Lab’s work, you know we are strong proponents of managing plant communities for forbs, or herbaceous broad-leaved plants. We do this because forbs provide high-quality food and are critical to a deer’s ability to fulfill their genetic potential. In previous articles we reviewed deer nutritional needs and how forbs can provide the minerals and nutrients that bucks need to optimize antler growth and how does require a high-quality diet during the summer months when they are producing fawns and lactating. Furthermore, we talked about ecological disturbance and how you can use habitat management tools like prescribed fire and forestry techniques to adjust the plant community to ensure you have enough forbs available on your property. The only chink in our deer habitat management armor is that forbs aren’t readily available year-round. That is, forbs are most common during the growing season (spring and summer) and less available during the dormant season (fall and winter). During the dormant season, browse is the most important food component.

How Does Browse Differ From Forbs?

We collectively lump vines, brambles/briars, and trees into deer browse. Bottom line, browse has a woody stem whereas forbs are herbaceous and more digestible. Although generally not as nutritious as forbs, many browse species still provide high-quality food and add to the diversity of plant species from which a deer can choose. What’s more, browse is typically available throughout the year.

What Do Deer Browse On?

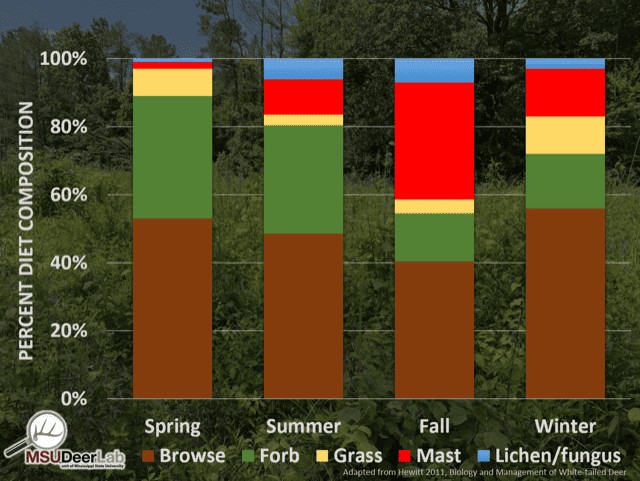

In parts of the whitetails’ range, vines such as greenbrier, Japanese honeysuckle, poison ivy, dewberry, and trumpet creeper are commonly selected by deer, and some are very good quality. For example, trumpet creeper can have crude protein values up to 27% during the spring. Shrubs and young trees make up the other component of browse. Deer commonly seek out species like American beautyberry, blackberry, blueberry, and blackgum. As you can see from Figure 1, browse makes up 40% of their diet during the fall, and close to 60% during the winter. But here’s the problem with many of the browse species – they are deciduous and lose their leaves during the winter. So, trumpet creeper or blackgum can’t provide meaningful forage biomass during the winter.

Figure 1: Seasonal change in white-tailed deer diet composition.

This seems like a really big issue for deer! Other than acorns, what’s a deer supposed to eat during the winter? Although there are some cool-season forbs and perennial warm-season forbs like goldenrod that have basal rosettes present year-round, they don’t provide much winter biomass. Some browse species like greenbrier and Japanese honeysuckle hold their leaves and provide a modest amount of forage during winter, but still only amount to a few mouthfuls here and there. This seems like quite a predicament for a large animal that relies exclusively on plant material for food, but sure enough, deer are adapted to this seasonal limitation.

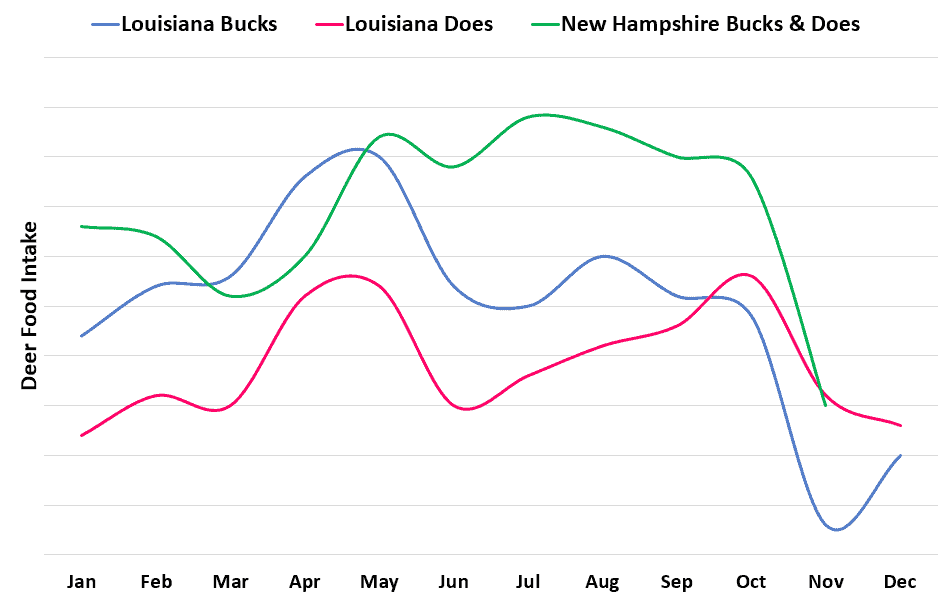

Deer just don’t require as much food during winter. Over the eons, deer have adapted to scarce food supplies by minimizing expensive life-history demands during winter. Although does are pregnant in winter, nutritional requirements are relatively low the first two trimesters of pregnancy and don’t ramp up until the 3rd trimester which overlaps with spring green up when high-quality forage is abundant. Likewise, bucks are in maintenance-mode in winter and recovering from the previous months of energetically demanding breeding activities. They don’t start antler growth until the springtime forage is there to support it. Figure 2 shows intake rates from a sample of southern (Louisiana) and northern deer (New Hampshire). In these feeding trials, deer had food ad libitum, meaning they could eat all they wanted. Seasonal variation in food intake is not because the researchers limited how much they could eat, it’s because the deer chose to eat more or less.

Notice intake rates for both southern and northern deer increase during the spring, but northern deer increased their intake about a month after the southern deer. This is likely because northern deer evolved where spring green up is later in the year. Interestingly, the southern bucks and does voluntarily restrict their food intake in June, July, and August but the northern deer do not. The southern decrease is likely a response to excessive summer heat, and every father knows that a late-term mom will eat less because their baby is taking up all the room. But northern and southern deer decrease intake in winter. This is an adaptation to lower food availability, and bucks have other things on their mind – the rut.

Figure 2: Seasonal change in white-tailed deer voluntary food intake (intake is relative to the deer’s body weight).

Deer Browse Takeaways

First, browse doesn’t get all the management fanfare, but it’s a critical component of a deer’s diet. As if a cement foundation is critical to the integrity of the house built upon it, browse is the foundation of deer diets. Forbs are the 2x4s, siding, and all the finish-work that go into the house reaching its full potential.

Second, it’s very easy to gauge relative deer density on your property by examining browse during the late winter. That’s a time of year when food is most limited, and evidence of deer use is most obvious. If every greenbrier or honeysuckle vine is heavily browsed, you likely need to harvest more deer, create more food, or both.

Third, managing for browse is no different from managing for forbs but browse may appear a few years later. In the last article we discussed plant succession and how herbaceous forbs respond very quickly after disturbance and browse appears a year or two later. So, no additional management technique is needed, just a little more time.

Fourth, cool-season food plots can be an important supplement to the native plant community. Of course, we all love food plots to attract, see, and hunt deer, but don’t neglect a food plot’s ability to provide high-quality food at a time of year when there’s not much food to go around.

Referenced Studies:

Join our weekly newsletter or subscribe to GameKeepers Magazine.

Your source for information, equipment, know-how, deals and discounts to help you get the most from every hard-earned moment in the field.