I’ve planted clover food plots from Missouri north to Manitoba, and the Dakotas east to Michigan and Quebec, but I have no experience in the South. So I asked the person who does have that experience, Austin Delano, who has planted just about anything you can think of for whitetails all over the South. Austin is Southern Field Services Manager and Head of Research and Development for BioLogic and is the person who I ask food plot questions to which I don’t know the answer.

Concerning Clover

If you manage property for whitetails or turkeys, you likely have some type of clover planted on your property. Many from our country’s mid-section and to the North consider it to be one of the cornerstones of a sound food plot program. Those in the South should feel the same way, it’s just a bit more difficult to care from our mid-tier states and to the south. The cooler, humid growing season in the Midwest, northern tier of U.S. states and Canada favors these legumes. Planting dates vary north to south and care for these highly nutritious, extremely palatable legumes is a combination of science mixed with art form, but they can be productive no matter where you manage whitetails. Different varieties are chosen for a range of characteristics to meet specific management goals and growing conditions, but clover should be in your program because of its wide range of payback.

Bonap.org

Perennial white clovers can provide years of quality, high protein, extremely attractive forage for your herd. There are white annual and biannual varieties, too. Red clovers tend to be a bit easier to grow in a wider range of conditions; however, they are typically not as attractive to whitetails as most white varieties. The best product for most gamekeepers will be a “blend” of several different clover varieties and possibly other perennials like alfalfa, trefoils or chicory. With a blend you not only extend the palatability timeframe of the stand, but you also protect yourself against failure due to specific growing conditions unfavorable to certain cultivars.

In the South, good perennial clover plots do really well, even in the heat so long as rainfall is adequate. A well-established perennial clover can go dormant under extreme heat and/or drought conditions and come back strong once the rain returns. The resilient root system of a well-established clover in a healthy soil allows it to withstand some extreme conditions.

As it is when planting anything for whitetails, moisture is the key determinant for success. As long as you receive 25 to 30 inches of rainfall annually you should be able to find perennials that will work for you. In drier or sandy areas, adding deep-rooted perennials like alfalfa and chicory to the blend will help dramatically in stand survival.

When maintained properly and planted in soil which is initially close to a neutral pH, perennial clover stands can persist for six to eight years or more. In more acidic soils because of the need to incorporate lime when the soil reverts back to being overly acidic, depending on your soil type and original pH you can expect more like three to five years from your crop and then you’ll need to incorporate lime again. It may also be suggested to rotate an annual into the same soil if you’re planning on putting clover back in the same ground.

When managed correctly, white clovers will spread by sending out a stem that grows horizontally along the ground surface called a stolon. The stolon will create nodes (a joint on a plant stem where a leaf attaches) where roots will form. This process creates “daughter plants” which will actually replace the original seedlings after a few years. So persistence is the greatest in the varieties that create the most stolons, which tend to be the small-leaf whites.

Renewal from seed is also possible. If the plants are not browsed heavily or mowed often they will flower and produce seed. Regeneration from seed helps longevity in areas with dry summer conditions (as in the south or west). Large-leaved types (like Non-Typical) perform best when they are mowed less frequently, or when browsing pressure is limited and plants are allowed to mature. Still, mowing is important, especially during the cooler times of the growing season.

Dave Medvecky

On the other hand, the small-leaved types respond better to frequent browsing and/or mowing. Large-leaved varieties grow taller and stand upright more than the small-leaved types. Small-leaved varieties typically have thick stolons and strong roots. Large-leaved types have fewer stolons and usually don’t regenerate or persist as long as medium and small-leaved whites. Thus, large-leaved varieties are also more apt to be un-rooted by browse pressure.

Medium-leaved types (like White Dutch) are, as you’ve probably guessed, intermediate in features; these perform well under a wider range of situations. Constant browse pressure is tolerated best by the small-leaved types. As said, small-leaved types do not grow as tall as the larger-leaved clovers, but they have numerous small leaves and many stolons so they are an excellent choice for areas that receive heavy browse pressure.

Given the different management necessities of the numerous varieties, before choosing which type of clover to plant, think about your growing conditions, your deer density in relation to the amount of acreage you will provide in clover, and what you will be able to do for a maintenance routine (how often you will be able to mow, spray with herbicides, fertilize, over-seed, etc.).

As an example, if you don’t have the resources to mow the plot frequently, especially during the spring when clover grows rapidly, or if the deer density is low in relation to the amount of acreage devoted, then a large-leaved form would be preferable. On the other hand, if you have the ability to mow the stand frequently during the spring and/or the deer density is high relative to the amount of forage, then a small-leaved type of clover would be preferable. The small-leaved types of clover perform best when the stolons are exposed to sunlight – which encourages daughter plant production at the nodes. This response ensures the stand is thick and new plants are constantly being produced, helping the stand to remain productive for many years.

The specific growing/management conditions will encourage the favorable cultivars of your blend to the forefront. One important consideration to note is that large-leaved clover doesn’t mean more tonnage per acre. The yield of most white clover types (large-leaved to small-leaved) is comparable if each variety is cared for properly.

Kenny Thompson

I suggest that your total perennial acreage be planted in stages so that it is not all the same age. If you replant, remember it means the field will not provide a good source of food for almost an entire growing season. Ground preparation and planting combined with waiting for germination and the time required for perennials to produce enough growth for deer requires a good portion of the growing season. By planting in stages you never need to eliminate all of your perennials at once.

Clover Food Plot Planting Times

Planting perennial clover is as easy as preparing a decent seedbed and broadcasting the seed at the appropriate rate. The seed should not be covered any more than ¼ of an inch. The ultimate would be if you could go over the broadcasted seed with a cultipacker or roller to ensure good seed-to-soil contact.

Perennials had been traditionally planted during the spring in the North, in the spring or early summer midway throughout the country, and during the late summer and early fall in the South. These planting times coincide with when the most moisture would be available ensuring the best survival for the crop. However, you can fudge with this planting time significantly, especially in the north and transitional areas. As long as you plant them early enough so they have the required time to develop their root systems you should have success. Perennial clovers need 45 to 60 days to establish a root system so they will indeed be “perennial” for you and return after dormancy. I must admit that on my home property in Minnesota, I’ve gone to planting clover more during the late summer simply because there is much less weed competition after the summer weed cycle is complete. But as said, moisture is the key determinant for success.

Caring for Clover Food Plots

Caring for Clover Food Plots

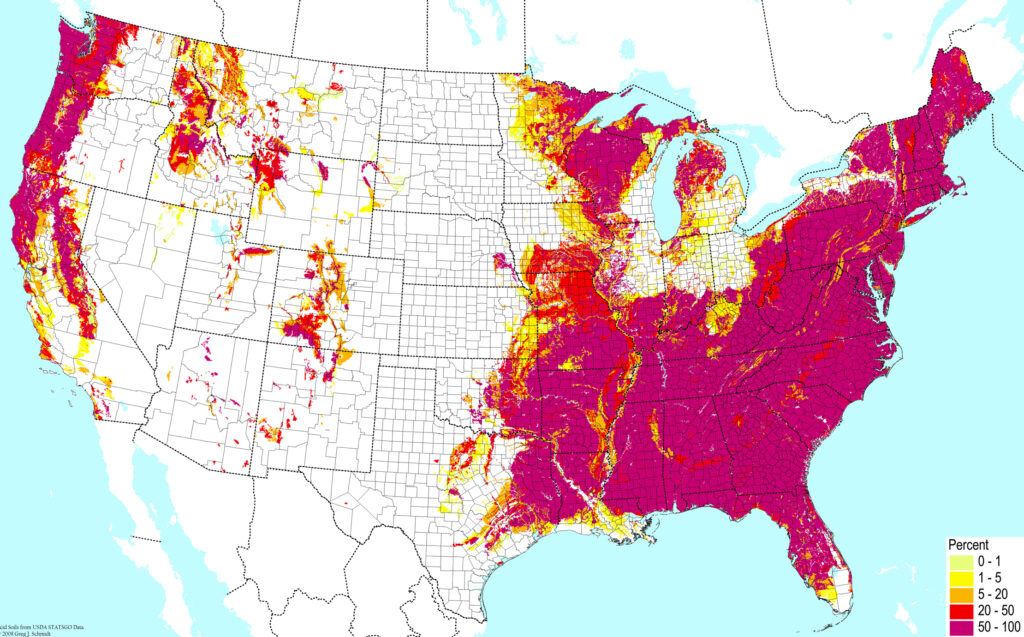

To maintain perennial clover, it isn’t as difficult as some think. In the South, the timing of mowing, planting and other maintenance is a bit more finicky. One reason clovers tend to be more difficult to care for in the South and along the eastern seaboard is because the soils tend to be more acidic. From Louisiana and Arkansas and northeast all the way up to Maine, soils tend to be more acidic than the Midwest and northern states. So to begin, it is important to neutralize any soil acidity. Soil pH has a big effect on the availability of nutrients to the plants. Aside from certain nutrients being bound in the soil so they aren’t available for the plants to use, in acidic soil (or low pH) some micronutrients can be present at levels toxic to clover. Legumes are particularly sensitive to acid soils. This means; do a soil test and incorporate the necessary lime to neutralize the acidity to bring your pH to 6.5 to 7.0.

Choosing the Proper Fertilizer

Choosing the proper fertilizer is also important. Clover can use both, atmospheric fixed nitrogen produced from its nodules, and mineral nitrogen from synthetic sources. When fertilizing, a blend with no nitrogen (N) is typically recommended, for instance, 300 to 350 pounds of 0-20-20 per acre. A balanced fertilizer with N (such as 10-10-10) can be used at planting time when establishing the clover, but after it’s established I would use zero N. Legumes produce their own nitrogen, if you add nitrogen to legumes you encourage other grasses and unwanted weeds to take root and you “train” your clover to be lazy. If you give it nitrogen it stops affixing its own. Fertilize your perennials at planting time and then again at least once per year after. It is best to fertilize according to the results from a soil test.

Mowing Clover

How often and how low you mow can greatly influence clover production. Frequent mowing during the spring favors white clover growth. Besides how often you mow, anotheraspect of white clover maintenance is how much of the plant’s height is removed during mowing. Some absentee land owners or people that simply don’t have the time or proper equipment, do not mow often enough — and when they do, because they are “there now andcan do it,” tend to mow too short at the wrong time.

Todd Amenrud

Infrequent mowing during the spring will allow the development of larger leaves. However, this results in less stolon production, fewer daughter plants and the loss of new growth. More frequent mowing, but not removing as much of the plant each time, will restrict total plant height, but enhances stolon survival and increases the stem density per acre. More frequent mowing typically equals a thicker, healthier stand that is more appealing to your herd.

Mowing at the correct time is possibly more important in the South. In hot or dry conditions, white clovers should not be mowed frequently and in some cases should even be left unmowed long enough to produce seed heads.

On my home property in Minnesota I typically mow frequently in May, June and into early July and then I watch it closely and mow when I feel that the crop can handle the stress. In July and August, I also do not mow as short as in the spring and early summer. During the hot, dry months I use the “rule of thirds.” I never mow any more than 1/3 the height of the plants.

With a perennial white clover blend, a good stand can be encouraged both, by frequent mowing during the cooler, moist periods to increase stolon production and survival, and no mowing during droughts or when the clover is growing slowly to promote seed production.

As mentioned, another option is to mix chicory and/or alfalfa into your clover food plot plantings. These perennials have a deeper root system than clover and will provide quality forage during dryer conditions. Chicory, in particular, thrives during hot, dry weather. So during a dry period, when white clover should not be mowed, the chicory will stand erect and provide a highly nutritious food source.

The use of herbicides may also be recommended to help keep the unwanted competition out of your perennial plots. I typically treat with a grass specific herbicide a couple times during the growing season. I tend to use a clethodim-based herbicide more often than other grass herbicides, but there are other acceptable chemical options.

Mowing tends to keep unwanted broadleaf weeds out of the plots, but there are also some options for herbicides to treat broadleaf weeds. Because clover itself is a broadleaf, controlling broadleaf weeds in clover by use of an herbicide is a little more challenging. 2-4-DB is the most commonly used herbicide for broadleaf control in clover plots. Pay attention to the “DB” in the name because it’s not the same as the common 2-4-D herbicide, which will kill clover! I must say in over 40 years of planting clover I have NEVER needed to use a broadleaf herbicide in a clover plot. A healthy clover plot is the best defense against competition.

Over Seeding Clover

One last detail that I suggest is to over-seed your perennial every couple of years. I typically over-seed at a rate of about ¼ of what I would do if I were originally planting the plot. This helps fill in gopher mounds, wheel ruts, spots where mowed foliage may have covered up and killed some plants and bare spots. It also adds new, young seedlings to the plot. I have had plots that have made it to ten years old that look every bit as good as they did in their second or third year. I cannot stress how important a perennial clover plot is to almost any food plot program whether it’s in the North or South.

Join our weekly newsletter or subscribe to GameKeepers Magazine.

Your source for information, equipment, know-how, deals and discounts to help you get the most from every hard-earned moment in the field.

Caring for Clover Food Plots

Caring for Clover Food Plots